Player FM 앱으로 오프라인으로 전환하세요!

What happened to the village, gardens and fish camp at Auke Rec?

Manage episode 421190509 series 1457379

Every other June, canoes — or yaakw — arrive at a beach in Juneau. With carved formline paddles in hand, Southeast Alaska Native people row for days to get there.

They come for Celebration, the gathering of Lingít, Haida and Tsimshian people honoring the survival of traditional dancing, art, language and community.

Seikoonie Fran Houston is a spokesperson for the Áak’w Ḵwáan. She spoke in a 2022 Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska video from the landing.

“The first one I saw that occurred — it brought tears to my eyes to witness this. And it also kind of gives you a little vision as to what our ancestors did,” Houston said.

But yaakw have been landing at this beach for much longer than the 40 years that have passed since the first Celebration. It’s the site of an old Lingít village called Aanchg̱altsóow. That means “the town that moved.”

A KTOO listener asked about the Áak’w Ḵwaan Village, fish camp, and garden that were once where Auke Recreation Area — or Auke Rec — is now.

Aanchg̱altsóow: ‘It’s a good place, it has plenty of what we need.’

Auke Rec is a park along a beach north of the rest of Juneau, with stone picnic shelters and fire pits. On clear days, the beach is dotted with couples on walks, dogs sniffing around, and families having picnics.

Thereʼs a section of the beach thatʼs sandier and smoother, down an unofficial trail in the middle of the beach. Oral tradition says it was cleared of boulders and large rocks for easier yaakw launches and landings.

By the time Seikooni Fran Houston was growing up, Áak’w people weren’t living at the village site, but she knows the story of how they first got there.

“When we migrated, that was the first area — so in other words, we were the first Indigenous people of the area,” she said.

The oral history has it that the Áak’w people migrated from the south and deeper in the interior. From a distance, the clan leader saw Aanchg̱altsóow and sent scouts to it, Houston said.

“And they came back and they told the leader, ‘It’s a good place, it has plenty of what we need,’” she said. “So that’s the real short story of a long story.”

For hundreds of years, Áakʼw people lived at Aanchg̱altsóow.

The Forest Service takes over

Houston said that around the turn of the 20th century, people had started moving away from the village to Douglas and downtown Juneau to work as miners, and so their children could attend school.

But she said the land at Aanchg̱altsóow was always in use.

“There was a time, too, that there were some people who stated that we abandoned Auke Rec,” she said. “We didn’t. We still use it. Not only do we use it — we take what we need in the area — we use it for ceremonies. We didn’t abandon it.”

In the 1920s, the United States Forest Service claimed the land was unoccupied. They began to make campsites, trails and other infrastructure in the area. Then, in 1931, the Forest Service claimed full ownership.

Juneau researcher Peter Metcalfe wrote “A Dangerous Idea: The Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Struggle for Indigenous Rights.” He said settlers claiming that land was “abandoned” was a common land-grab tactic.

“That has been used in a legal sense against Native Americans from the beginning of contact in the Lower 48, as well as Alaska,” he said. “Most Native Americans would say ‘We never abandoned our land.’ And it’s true, in a moral sense. If we own something, and we haven’t sold it, we still own it. It doesn’t matter if we live there or not.”

During the same year when the Forest Service took control, over a dozen Áak’w Ḵwáan built cabins on the old village site to stake claim to the land. It didn’t work. In January 1932, a federal judge ruled that Lingít people had given up ownership by not occupying the land.

The judge gave the families a month to remove their cabins. Afterward, the Forest Service expanded their construction at the site, and by the 1940s, it looked much like it does today.

Metcalfe said the way the federal government claimed Auke Bay wouldn’t hold up today.

“The Forest Service was wrong about Auke Bay. When they thought they had won, they hadn’t really. They just put off a decision that was finally resolved in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971,” he said.

‘Thereʼs no trace, except for those footprints’

Sitting on the beach on a sunny March day, Saan Jeen Jennifer Quinto was getting ready to lead a traditional ocean dip. After setting an intention and reflecting around a fire, Quinto guided participants into the water a little bit at a time.

Quinto said that, to her, Aanchg̱altsóow is a direct connection to her identity as Alaska Native.

“For me, thereʼs different layers of not only sacredness, but all the different emotions of life,” she said. “The way that this was also likely a place of joy for a lot of people, but also the heartache of the fact that weʼre not allowed to be connected in that way any longer to this place.”

She said the word “recreation” in “Auke Recreation Area” can cause people to treat the beach like itʼs a playground.

“I don’t think the way that itʼs currently used or represented just doesnʼt — people donʼt understand all of those layers that are happening here for those of us from the Native community,” Quinto said

Quinto said sheʼs often picking up trash from the sites of old longhouses. Indentations are still present in the trees along the shore.

“It always crosses my mind that people are respectful of gravesites, and in a lot of ways this area has that same sort of sacredness,” she said.

And Aanchg̱altsóow is a gravesite. In a 1987 Alaska Department of Natural Resources cultural resources survey, archeologists reported finding at least one set of human remains there.

Quinto said that if people could only see what it looked like when it was a lived-in village, they might treat it differently.

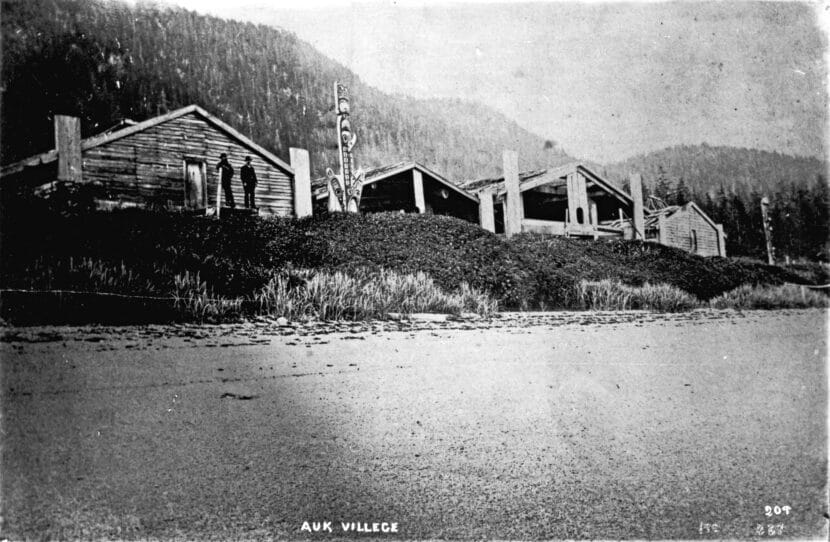

“You would have seen the house fronts, you would have seen the kootéeyaa, you would have seen our people out here. And now thereʼs no trace, except for those footprints,” she said.

She said that erasure was the start of a long history of reducing the footprints of Lingít people in Juneau — including the gradual shrinking of Juneau Indian Village downtown in the middle of the last century and the burning of Douglas Indian Village in 1962.

But events like traditional dips in the ocean and the canoe landings at Celebration bring Lingít traditions back to the land, and back to life, Quinto said.

“For Lingít people, we believe that everything has its own spirit, and has its own life,” she said. “And so, to me, when weʼre able to gather here for cultural events, those are moments that we get to restore that life to this area, and I donʼt think it happens enough.”

Seikoonie Fran Houston said that when she stands on the beach now, it fills her with gratitude for her ancestors.

“I go out there and I talk to my ancestors and I thank them every time I go out there,” she said. “Saying thank you for choosing this area, because it’s so pretty and so peaceful.”

Next week, paddlers will once again ask the Áak’w Ḵwáan for permission to come ashore, in recognition for the history and life of this piece of land.

Curious Juneau

Are you curious about Juneau, its history, places and people? Or if you just like to ask questions, then ask away!

- What do you want to know about Juneau?

- Name*First Last

- Email*

- Phone

- Zip Code ZIP / Postal Code

- CAPTCHA

20 에피소드

Manage episode 421190509 series 1457379

Every other June, canoes — or yaakw — arrive at a beach in Juneau. With carved formline paddles in hand, Southeast Alaska Native people row for days to get there.

They come for Celebration, the gathering of Lingít, Haida and Tsimshian people honoring the survival of traditional dancing, art, language and community.

Seikoonie Fran Houston is a spokesperson for the Áak’w Ḵwáan. She spoke in a 2022 Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska video from the landing.

“The first one I saw that occurred — it brought tears to my eyes to witness this. And it also kind of gives you a little vision as to what our ancestors did,” Houston said.

But yaakw have been landing at this beach for much longer than the 40 years that have passed since the first Celebration. It’s the site of an old Lingít village called Aanchg̱altsóow. That means “the town that moved.”

A KTOO listener asked about the Áak’w Ḵwaan Village, fish camp, and garden that were once where Auke Recreation Area — or Auke Rec — is now.

Aanchg̱altsóow: ‘It’s a good place, it has plenty of what we need.’

Auke Rec is a park along a beach north of the rest of Juneau, with stone picnic shelters and fire pits. On clear days, the beach is dotted with couples on walks, dogs sniffing around, and families having picnics.

Thereʼs a section of the beach thatʼs sandier and smoother, down an unofficial trail in the middle of the beach. Oral tradition says it was cleared of boulders and large rocks for easier yaakw launches and landings.

By the time Seikooni Fran Houston was growing up, Áak’w people weren’t living at the village site, but she knows the story of how they first got there.

“When we migrated, that was the first area — so in other words, we were the first Indigenous people of the area,” she said.

The oral history has it that the Áak’w people migrated from the south and deeper in the interior. From a distance, the clan leader saw Aanchg̱altsóow and sent scouts to it, Houston said.

“And they came back and they told the leader, ‘It’s a good place, it has plenty of what we need,’” she said. “So that’s the real short story of a long story.”

For hundreds of years, Áakʼw people lived at Aanchg̱altsóow.

The Forest Service takes over

Houston said that around the turn of the 20th century, people had started moving away from the village to Douglas and downtown Juneau to work as miners, and so their children could attend school.

But she said the land at Aanchg̱altsóow was always in use.

“There was a time, too, that there were some people who stated that we abandoned Auke Rec,” she said. “We didn’t. We still use it. Not only do we use it — we take what we need in the area — we use it for ceremonies. We didn’t abandon it.”

In the 1920s, the United States Forest Service claimed the land was unoccupied. They began to make campsites, trails and other infrastructure in the area. Then, in 1931, the Forest Service claimed full ownership.

Juneau researcher Peter Metcalfe wrote “A Dangerous Idea: The Alaska Native Brotherhood and the Struggle for Indigenous Rights.” He said settlers claiming that land was “abandoned” was a common land-grab tactic.

“That has been used in a legal sense against Native Americans from the beginning of contact in the Lower 48, as well as Alaska,” he said. “Most Native Americans would say ‘We never abandoned our land.’ And it’s true, in a moral sense. If we own something, and we haven’t sold it, we still own it. It doesn’t matter if we live there or not.”

During the same year when the Forest Service took control, over a dozen Áak’w Ḵwáan built cabins on the old village site to stake claim to the land. It didn’t work. In January 1932, a federal judge ruled that Lingít people had given up ownership by not occupying the land.

The judge gave the families a month to remove their cabins. Afterward, the Forest Service expanded their construction at the site, and by the 1940s, it looked much like it does today.

Metcalfe said the way the federal government claimed Auke Bay wouldn’t hold up today.

“The Forest Service was wrong about Auke Bay. When they thought they had won, they hadn’t really. They just put off a decision that was finally resolved in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971,” he said.

‘Thereʼs no trace, except for those footprints’

Sitting on the beach on a sunny March day, Saan Jeen Jennifer Quinto was getting ready to lead a traditional ocean dip. After setting an intention and reflecting around a fire, Quinto guided participants into the water a little bit at a time.

Quinto said that, to her, Aanchg̱altsóow is a direct connection to her identity as Alaska Native.

“For me, thereʼs different layers of not only sacredness, but all the different emotions of life,” she said. “The way that this was also likely a place of joy for a lot of people, but also the heartache of the fact that weʼre not allowed to be connected in that way any longer to this place.”

She said the word “recreation” in “Auke Recreation Area” can cause people to treat the beach like itʼs a playground.

“I don’t think the way that itʼs currently used or represented just doesnʼt — people donʼt understand all of those layers that are happening here for those of us from the Native community,” Quinto said

Quinto said sheʼs often picking up trash from the sites of old longhouses. Indentations are still present in the trees along the shore.

“It always crosses my mind that people are respectful of gravesites, and in a lot of ways this area has that same sort of sacredness,” she said.

And Aanchg̱altsóow is a gravesite. In a 1987 Alaska Department of Natural Resources cultural resources survey, archeologists reported finding at least one set of human remains there.

Quinto said that if people could only see what it looked like when it was a lived-in village, they might treat it differently.

“You would have seen the house fronts, you would have seen the kootéeyaa, you would have seen our people out here. And now thereʼs no trace, except for those footprints,” she said.

She said that erasure was the start of a long history of reducing the footprints of Lingít people in Juneau — including the gradual shrinking of Juneau Indian Village downtown in the middle of the last century and the burning of Douglas Indian Village in 1962.

But events like traditional dips in the ocean and the canoe landings at Celebration bring Lingít traditions back to the land, and back to life, Quinto said.

“For Lingít people, we believe that everything has its own spirit, and has its own life,” she said. “And so, to me, when weʼre able to gather here for cultural events, those are moments that we get to restore that life to this area, and I donʼt think it happens enough.”

Seikoonie Fran Houston said that when she stands on the beach now, it fills her with gratitude for her ancestors.

“I go out there and I talk to my ancestors and I thank them every time I go out there,” she said. “Saying thank you for choosing this area, because it’s so pretty and so peaceful.”

Next week, paddlers will once again ask the Áak’w Ḵwáan for permission to come ashore, in recognition for the history and life of this piece of land.

Curious Juneau

Are you curious about Juneau, its history, places and people? Or if you just like to ask questions, then ask away!

- What do you want to know about Juneau?

- Name*First Last

- Email*

- Phone

- Zip Code ZIP / Postal Code

- CAPTCHA

20 에피소드

모든 에피소드

×플레이어 FM에 오신것을 환영합니다!

플레이어 FM은 웹에서 고품질 팟캐스트를 검색하여 지금 바로 즐길 수 있도록 합니다. 최고의 팟캐스트 앱이며 Android, iPhone 및 웹에서도 작동합니다. 장치 간 구독 동기화를 위해 가입하세요.